Tribe Tribune writers struggle with moms’ deaths

March 17, 2022

Senior Cooper Davenport’s mother died from COVID this year. Senior Nick Arnold lost his brother to suicide. The Tribe Tribune staff reached out to both young men to see how they were doing. Cooper said grieving felt “like being homesick to a person.” Nick said, “Don’t expect to get over it quickly. They try, but my friends just don’t understand how I’m feeling.” As we discussed the topic of loss in the newsroom, we realized that two of our staff members were also dealing with grief. Sophomore Reagan Glidewell was sliding back into depression three years after her mom’s death. Senior Macayla Short was still carrying raw emotions from her mom’s recent death. Despite their pain, both reporters felt compelled to tell their stories. They hope others will see they are not alone. We’re grateful for their brave honesty.

Sophomore says grief process takes years

I was in fourth grade when my mom was diagnosed with stage 4 breast cancer. It was hard to accept that Kelley Glidewell—the loudest parent cheering from the stands, the brightest mom with big earrings and infinity scarves—could be sick. Despite it all, during her chemotherapy my family hosted her shaving party, all of us taking turns shaving off her hair—first with a reverse mohawk and crazy designs, then completely bald—to avoid watching her daily hair loss.

Even after surgery, her remission lasted only a few months. The monster spread to her bones. It couldn’t be cured, but it was treatable.

She continued to be the best mom, making Peter Pan and His Shadow costumes for me and my brother for Halloween and pulling us out of the car to look at Christmas lights.

But normal didn’t last.

The worst came during seventh grade. I was cast as Belle in Beechwood’s production of Beauty and the Beast. Finishing my final rehearsal, I learned my mom had been rushed to the hospital for a tumor clot that had to be drained. My mom, who should have stayed in the hospital, hauled herself to the play’s opening.

A week later, my mom stopped the treatments that were now killing her. With no other options, she said to me, “I am going to die.”

My sister was 7. She cried but mostly because she didn’t understand what was happening. My brother was 15. He was quiet, withdrawn. No tears, just staring.

We took her home. The doctor said she would live a few more weeks—through Christmas. She didn’t.

The day after she died, the empty hospice bed sat in our living room. Even though I was surrounded by family, I never felt so alone. The only person’s hug who could comfort me was gone.

Thoughts of the future overwhelmed me. My first school dance. My high school graduation. My first job. My wedding day. She wouldn’t be there.

Life got hard fast. I was angry. Not just moody, but furious at the world.

Things weren’t great between me and my dad, but it was worse with my brother. We fought daily with screaming and slamming doors. I knew it wasn’t true, but it felt like we truly hated each other. Coping with loss in completely different ways, my brother and I couldn’t understand each other.

I poured myself into school and sports, dealing with my pain with exhaustion. With honors classes, two sports, church, I had no breathing time. Dedicating the things I love to my mom—writing “KG” on every racing swimsuit and writing “KG” on my hand before every running event—I thought it would get easier. It didn’t.

My brother was the exact opposite. He disengaged from the world. He gave up on school, quit his extracurriculars, and just sat in his thoughts.

I saw his pain as laziness. He saw my pain as moving on.

In truth, I was far from moving on. Last year I was diagnosed with clinical depression and an anxiety disorder. These past four months have been the hardest. Instead of relaxing, I spent down time overthinking, especially obsessing about my looks. I stopped eating, lost 10 pounds and lost joy for life. I even tried to overdose on prescription drugs. Yes, drugs.

I know it’s hard for my friends to believe that I nearly killed myself, but it’s true. Even the straight-A, top-notch athlete with the constant smile can hit rock bottom. That’s the power of grief.

I’m doing better now, but it’s not easy. I restarted therapy and rebuilt family relationships. But remember, it was 1,095 days after my mom died when I needed the most help.

I’ve been told that grief takes many forms, but I wasn’t expecting to have such hard relapses into depression three years later. Yet I’ve come to realize that I need to accept grief the same way I accepted my recent foot injury.

I first injured my foot in November during a 1600 time trial. The doctor said to take a couple weeks off, but two weeks later, I felt the same pain. I tried to prioritize rest, waiting another few weeks. However, with just a few jogging steps, the pain in my foot persisted and eventually led to a stress fracture. I was out another six weeks.

Grief is an injury that persists. You make progress and it seems as if everything is fine, but one wrong move and you reinjure yourself. You can get reinjured over and over again, and each time you fall back, recovery takes a bit longer.

As hard as it’s been for me, it can be just as tough watching a friend struggle with grief. It’s hard to understand why one moment your friend is laughing and the next second they go quiet. Or why they can’t get out of bed one day and the next they’re out being social.

You can help in small ways. A simple smile or a “I’m proud of you” can help someone feel loved, known, and wanted when they feel so alone. Even just the presence of a friend can help bring a sense of safety and relief from being with their thoughts and feelings.

The reassurance that they seem to beg for can feel excessive. They also may overreact to minor conflicts. Just remember that loss is traumatic. Be patient.

You can try to put yourself in their shoes, but accept you will never truly understand what it’s like. Loss is complicated. Remember that even if your friend isn’t on crutches or wearing a cast, they still might be broken. Grief has its own timeline for recovery.

Senior feels emotions of love, anger, guilt

I lost my mother to a heroin overdose on Halloween night—just five months ago. At first I didn’t know how to react. I cried but it didn’t feel like it was real. My father held me as I mourned but my skin became numb and my brain felt electrocuted.

I remember—when I was only 9— having to check her pulse, bathe her and feed her when she was using. Before she left this world, I told myself that it would be easy, that death would happen and because I was angry with her, I’d get over it. I was angry at her because of the trauma she induced while under her so-called supervision.

Growing up in a druggy hoarder home, with a lawn chair for a bed, I had every right to be angry, but my anger turned to guilt. I felt pity and self hatred; somehow I believed I let this happen to her. Logically I knew I wasn’t responsible for her, but I regretted leaving her when I was 13 to move in with my dad.

I screamed and cried at myself because I felt so worthless. I wished I could just rip my body into two. I reread messages she sent me just days before she died, looking for some sort of clue to how I could have saved her. But there wasn’t anything to do. I’m a child, and she’s an adult who chose drugs. Knowing the truth didn’t make me feel better.

The day after my mother died, I went to school absolutely broken. I completed few assignments and it was difficult talking to friends without crying uncontrollably. Nothing felt real in those moments. I felt numb. I walked through the halls with a blank face matching my thoughts. My grades dropped. Motivation and a will to go on seemed to dissipate. I was beyond stressed. I worried and worried but I did nothing to fix it, I had no energy to spare. In my head it was just like what’s the point? To me there was no point.

Taking care of my mother until I was 13 was difficult, but that’s what made me attached. I loved her, and now that person I loved is gone. She can’t ever hug me, tell me it will be alright, the warm motherly touch is gone forever. And as challenging as our lives were, we had a close connection like no other, which was hard for people to understand.

Before the addiction to heroin and meth started, she was addicted to medication: vicodin, oxycontin, morphine, and xanax. It didn’t affect her behavior much, but she would lie in bed most of the time. During this time, my mother and I were always together.

My mother and I had many great memories together. Whenever we baked a cake she’d rub the frosting on our noses and kiss my forehead. She had taken hours of the day to hold me and talk to me when she had no energy. She made sure I knew she loved me. I know she wanted to be a mother, I know she loved me, but getting pregnant at 17 may have been a rough start.

It has been almost five months since she passed and I continue to have good and bad days. I’m starting to get back on track and I can feel myself coming back to life. Often, I get flashbacks of past events, but I’ve come up with ways to cope. I still haven’t fully accepted her death, but that takes time and I’ve got my whole life to forgive and acknowledge.

Often, I text her phone number telling her I miss her knowing I will get no response. Somehow I feel that she is there watching me reach out to her. I need her to know I care. But that is just how I cope.

You heal on your own time. No one heals the same. Anger, guilt, depression, anxiety are just a few of the emotions a person suffering with loss might feel. A person who has lost someone needs all the support you can give.

Grief counseling can help, but sometimes people need to work through the confusing range of emotions before they’re ready for therapy.

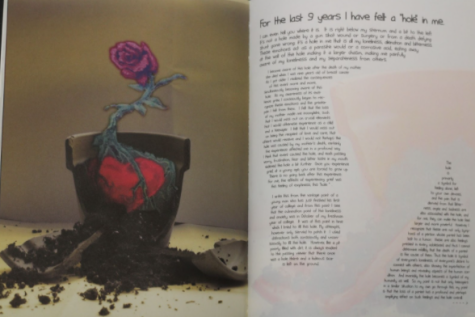

Sometimes reading can be the step between experiencing loss and going to therapy. FUHS counselor Erin Defries lost her father to cancer. She often recommends Love Sick published by Cancer Connected in 2008. The book is a collection of stories, art, poems that allow teens to help teens know they’re not alone—that there are other teens who understand grief.

There’s also Lynne B. Hughes’s You Are Not Alone: Teens Talk About Life After the Loss of a Parent. The book combines advice about coping with loss as well as pages of quotes from real teens, including ones like this: “When my mother finally died after being sick for almost two years, I was relieved, and this made me feel so guilty. I wasn’t relieved that she had died, but I was relieved that I wouldn’t have to see her so sick anymore. I was guilty then, and I still am, but I understand more now that it is okay to feel this way.”

Books like these are helpful in recognizing that the loss of a parent isn’t something that you get over. It’s something that becomes a part of you.

And the best we can do is manage a peaceful coexistence with our loss.