Being Mexican isn’t a crime, and neither is lowriding

March 13, 2023

Note from the editor: These heartfelt stories by reporters Elany Zavala and Madison Dominguez should be able to stand alone. Yet, I realized that not enough people have the context or education to understand them without prior knowledge. As Managing Editor, I decided to step in and provide historical context. As a Latina myself, I am used to having to explain my culture, oftentimes to avoid judgment. Minorities are tired of constantly having to explain themselves. Take the opportunity to read this, educate yourself, and learn about new cultures.

The History

Lowriding origins can be linked to the 1940s following World War II. Contrasting the “hot-rod” trend, Mexican-American veterans used their training to make their cars slower and lower rather than hotter and faster. Stylish flair was added by painting the outside of the car in a pre-Columbian art style.

“Low and slow” spread like wildfire in the area surrounding Los Angeles. The political side of lowriding gained traction in the 60s and 70s. The Chicano movement incorporated lowriding as a way to honor their Mexican-American culture.

Additionally, car clubs became involved in community services, supporting worker unions and helping to provide food to the community. The low-riding community became less about cars and more about helping society.

Through the 80s and 90s, the inclusion of lowriders in the rap scene perpetuated the connection between cruising and gangs. If your car is low, it doesn’t mean you are in a gang. But if you are in a gang, your car is low.

Moral of the story: lowriding has a rich history that is, unfortunately, being overshadowed by incorrect, often racially charged assumptions.

‘Brown Pride’

In her story below, reporter Elany Zavala mentions a car club her dad is a part of called “Brown Pride.” If you are unfamiliar with the term, it might sound like a form of racial inequality. However, that couldn’t be farther from the truth.

“Brown Pride” is not racist. Like lowriding, it is synonymous with the Chicano movement. Many compare “white pride” to “Brown Pride,” which is absurd to people familiar with the movement. Unlike white pride, brown pride is not a reactionary group combatting the Black Power movement. Instead, it’s a celebration of Latino heritage.

This past January, Caldwell High School student Brenda Hernandez in Idaho was given a dress code violation because her “Brown Pride” hoodie was seen as racist. According to the school’s principal, Hernandez and about 100 of her fellow classmates protested the violation by dressing stereotypically Chicano. Rosaries, bandanas, and Brown Pride apparel were confiscated because of their “violent connotation.”

Religious beads are in no way encouraging violence. If anything, wearing safe clothing items as a form of peaceful protest is protected under the 1969 court decision of Tinker vs. Des Moines. The assumption that Latino culture is inherently causing a disruption is harmful.

Finding security in my Chicana identity

Growing up, I always felt out of place. I knew on paper what my ethnicity was, but I didn’t feel like I had permission to engage with my own culture. As a Mexican-American girl, I constantly had one question on my mind: “Where the hell do I fit in?”

Even though California is an extremely liberal state, I’ve had to deal with people’s racism my whole life. I was born in Fullerton. My parents were both born and raised in Fullerton, and even attended Fullerton Union High School. Regardless, my most impactful experiences with racism have been at school.

Due to a lisp and my shy personality, my elementary school teachers and peers believed I didn’t speak English. Yet, English is my first language. I don’t speak any Spanish.

When I was 7, my mom, my sister, and I moved to Tennessee to live with my step-dad and his three sons. If anything, that made my relationship with my identity even more confusing. At my school in Tennessee, there were very few Mexican students and even fewer Chicanas. Me and the two other Mexican students became really close.

To most of my friends, I was their token Mexican. Even so, I didn’t live up to their expectations. I don’t speak Spanish, I like very few Mexican dishes, and I’m progressively getting less and less tan.

Moving back to California didn’t make it easier. The lack of diversity in my Tennessee elementary school made my first day at Nicolas Junior High a culture shock.

Yet, I quickly realized I still didn’t fit in. But this time it was because I wasn’t Mexican enough. I was– and still am– seen as the white-washed “fake beaner” of every friend group. When I’d mention not liking some Mexican foods, kids around me would be in utter shock. I’ve heard “How are you a beaner if you don’t like beans?” multiple times from multiple people.

My former best friend once told me that I benefit from my skin color, even though I wasn’t any lighter than her. She even swore that I wasn’t Mexican because I didn’t speak Spanish. Yet, a few months prior, she had won a Speech and Debate competition for a piece about how there isn’t one way to be Mexican. She had even said the words “Mexicans are still Mexican even if they can’t speak Spanish.”

The entire time I was struggling with my identity, I was also adjusting to a new relationship with my step-dad, Beto Millan. At the time, he was just my mom’s boyfriend. Even though I knew he was supposed to be my father-figure, I just couldn’t bring myself to call him “dad.”

Since age 12, my dad has been involved with gangs. He didn’t want to be in a gang but needed to be to protect himself. Yet, being in a gang prevented him from doing what he loves. Lowriding has his heart. Unfortunately, at the time he couldn’t go to car shows for fear of other gangs showing up.

Yet, over the years gang activity calmed down. After joining our family, he no longer needed to hide himself. He didn’t need to fear being in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Back in California as a family and no longer fearing the dangers of gang life, my dad took us all to his first car show in Santa Ana. It was a dream come true for him, feeling safe while doing the thing he loves with the people he loves.

After watching my dad finally achieve his dream, I opened up to him about how out of place I felt. I was surprised to hear him say that he felt the same way growing up. He was too Mexican for Fullerton, but too Chicano for Mexico.

At that car show, we finally felt like we had a place. There’s no hate, no judgment, and nobody tells you that you’re too Mexican or not Mexican enough. Everyone shares the same passion for their cars. It was the first thing that made me feel comfortable in my Chicana identity.

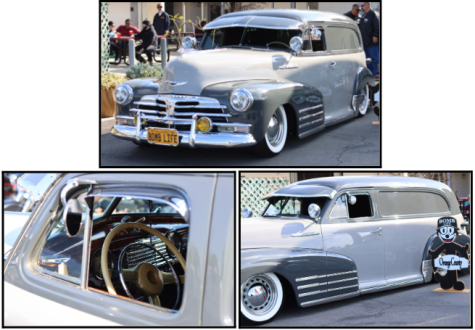

My dad spent eight years building his truck. He was so nervous when he entered it into competition, fearing he might lose in front of his family. What he didn’t understand was that we were all proud of him regardless of the competition. My younger brother even snuck off to buy him a model figure that looked similar to his truck.

We all wore matching shirts with the name of the car club on it, “Brown Pride.” We watched joyfully as other attendees stopped to admire and take photos of his truck. My dad does not like having his photo taken. But when he won second place for his 1949 Chevy pickup truck, he proudly smiled and posed with his trophy.

It’s the moments like these when I truly fit in. No one is better than anyone else, and no one is not enough. Everyone gets to be who they are and be proud.

The misconception that a Mexican lowrider-owner is automatically a gang member is harmful. My mom says that Mexicans don’t care about the stereotypes people have, and even take pride in the behavior that people misconstrue. While that is true, people can still negatively affect the Chicano community by pushing this false narrative.

Mexican people are disproportionately approached by law enforcement when seen in certain types of cars. Lowriding is not hurting anyone, and the goal of “Brown Pride” isn’t to make anyone feel less than. It is more so to lift Chicanos up and encourage us to embrace our culture.

Pride for both cultures

Being invited to my first car show by Elany was the Chicano experience I never knew I lacked in my life.

Both of my parents were born and raised in Mexico. I always felt that my Mexican side never correctly blended with my American side. I was not Mexican enough. I was not American enough. However, on Jan. 28, I was accepted by a community of people who grew up in an environment similar to mine.

On Chapman Ave. and just west of State College Blvd. I met many Mexican Americans who were representing their Chicano pride and lifestyle.

The more I spoke with each person and heard their stories of family or mistreatment the more I felt understood. Not being Mexican enough or being American enough was a universal experience within all of us.

This experience built a strong connection to bring our family’s Mexican culture and our American culture into one called Chicano culture.

Elany and I looked at the cars near where her dad parked his truck. These are some of the many cars that showed up at the Puro Amor car show.

While at the car show, I met and interacted with many different people with unique experiences. However, there were two stories of Mexican Americans that stood out to me whose lives have been influenced by their love for cars and their embrace of Chicano culture.

Christina Martinez is 69 years old and has been a resident of Fullerton for 35 years. The license plate on her car is in honor of her late son Anthony, whose nickname was Ant.

Ant graduated from West Covina High and was going to college. While driving home he was rear-ended by a drunk driver and passed away. In Anthony’s memory, Christina has dedicated her car to him.

A Fullerton resident discovered his love of cars through his older brothers. He got his 1948 Sedan Delivery 18 years ago and has slowly worked on it ever since.

One of his modifications is the interior wood grain. The original didn’t have wood grain, but he took inspiration from the cars his brothers owned and added it himself.

I’m insecure when it comes to speaking Spanish, the color of my skin, and my lack of knowledge of Mexican culture. These set me apart from my family. But with this Chicano culture, I experienced a place that embraces and balances both the American and Mexican sides of me, and I am proud to be Chicana.