As Tribe Tribune managing editor, I keep a low profile. I edit, take photos, and upload stories.

During my junior year as a features editor, I found myself enjoying taking photos more than writing. I photographed every event I could: assemblies, gallery shows, dance concerts. My favorites were theater dress rehearsals. A free show to help promote the performing arts department? Win–win.

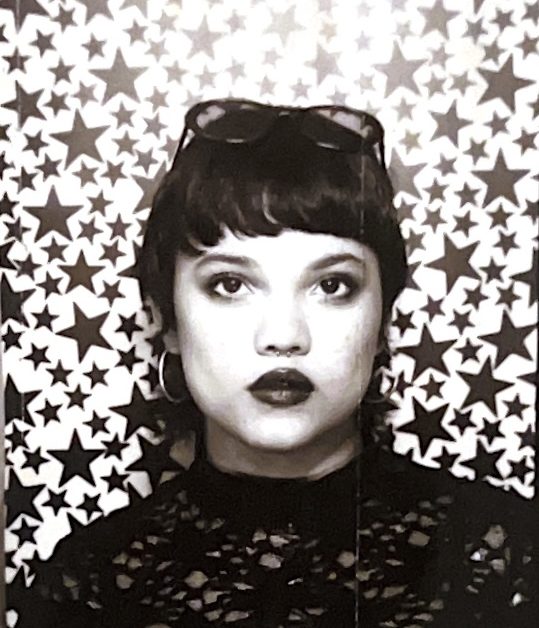

When this spring’s musical was announced, Tribune co-editor-in-chief Kitty Martinez said, “Oh, my God. They’re doing Chicago. There are going to be so many girls auditioning. And hardly any guys.”

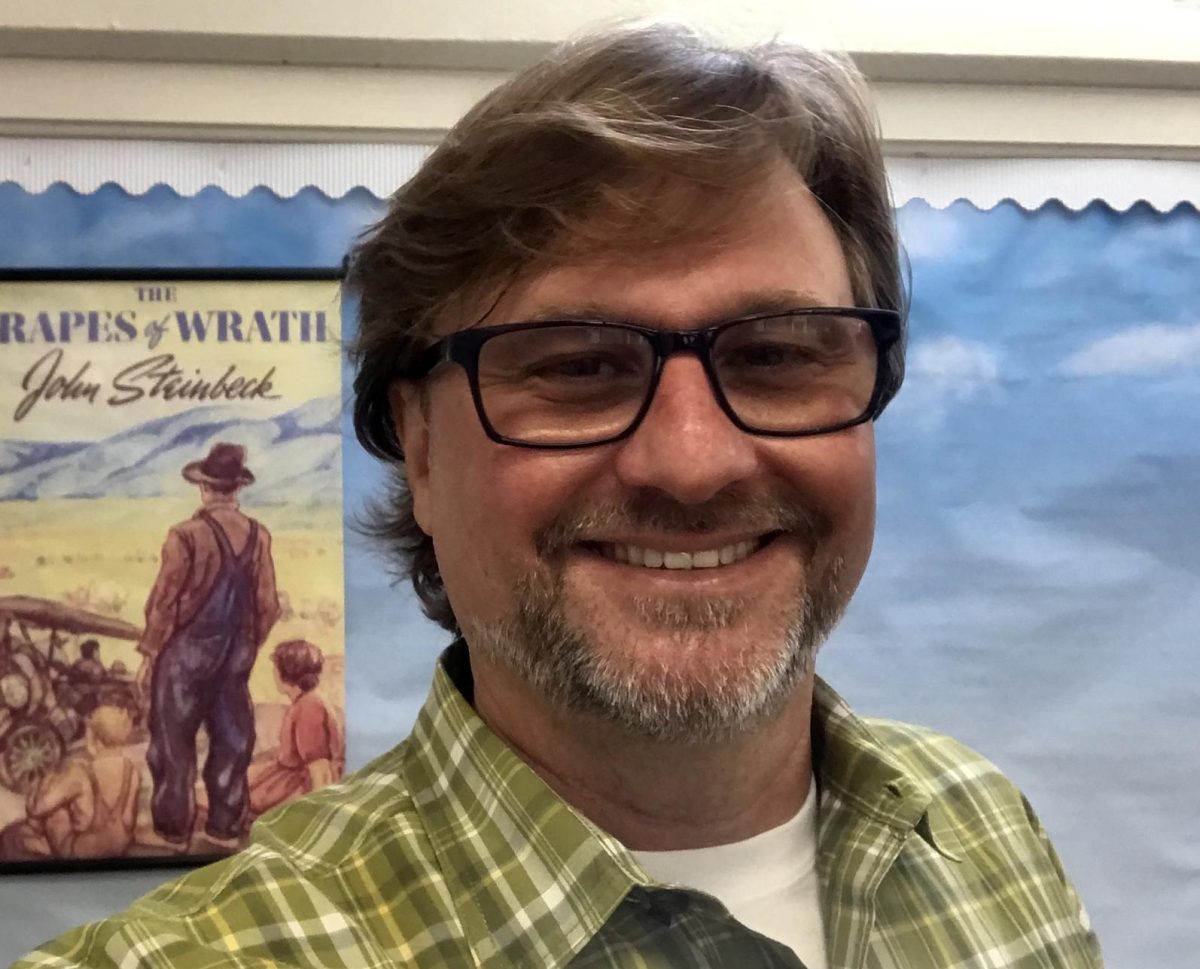

Journalism adviser Kimberley Harris said, “Why don’t we have a guy with no theater experience audition for the musical?”

The Tribune staff talked it out. The perfect candidate? Energetic and enthusiastic freshman reporter Dante Diaz. Of course, Diaz couldn’t. He had sports commitments.

The second-most perfect candidate? The complete opposite. A total not-on-stage guy. No attraction to the material. No desire to dance. Vocally monotone. A straight-laced introvert, responsible but otherwise unsuited for theater, both musical and regular. In short: Me.

Not so fast. I explained that I’d actually been on stage before. In the mandatory end-of-the-year 5th grade play, I was the lead. I was George freakin’ Washington, President of the United States. The rest of the Tribune staff agreed that this experience was irrelevant. I was outvoted. I’d get a part, and they’d be right. This is that story.

Yet I wasn’t the only Tribune staffer on this Chicago journey. Kitty herself was one of the many girls auditioning. Tribune campus arts editor senior Evelyn Ishikawa played the flute in the orchestra. Reporter junior Eadyn Ochoa was a member of the costumes team. Arts editor junior Sophia Goldblatt was a house manager. The difference, of course, was that they had some sort of experience in their respective fields. As a true outsider of the arts, I would have a far different journey.

NOTE: Included in this column are photos from other FUHS productions. This is not an editing error. The photos are a reminder that my theater experience before Chicago was that of theater photographer rather than performer.

Before anything, Kitty insisted I watch the 2002 film Chicago. Kitty and Evelyn Ishikawa got so into singing along with the film that I found following it difficult. It didn’t matter, really, since there was only one role for me to shoot for: Amos Hart, the loveable, honest, spineless dude who gets taken advantage of. Reasonable, I thought. Just one song and a fair number of lines. I’m no Billy Flynn.

I couldn’t audition without preparing, though. Harris had pitched the idea so her son Preston, 21 and a Cal State LA junior majoring in theater and himself a musical theater veteran, taught me some basics. Turns out singing isn’t just screaming and hoping you sound good. Enunciating lyrics is important as is singing from the diaphragm and getting your tongue out of the way of your words. I was better than I expected to be. Not good, of course, but passable for someone with zero singing experience.

Then, on the Tribune adviser’s orders, I took five lessons with Preston’s vocal coach Melissa Lyons. A great singer and teacher, Lyons’s reputation alone calmed many of my fears about auditioning. I wouldn’t be great, but Lyons would make sure I wasn’t an embarrassment. From her I learned more techniques, like imagining reaching for a note rather than hitting it or playing it. Lyons brought home the idea that musical theater is not just singing but acting and that your role’s physicality informs your singing.

I signed up to be the first one to audition. I convinced myself this showed confidence, but I knew that I just wanted it over with. Still, I sang my heart out.

After striking a pose and catching my breath, Chicago director Michael Despars told me to do it again but sadder. I did so, slightly frazzled but still trying.

I wasn’t great, but I did my best.

Dance auditions were the next day. It’s not a musical without dancing, after all. Gals outnumbered guys about 5 to 1. Everyone else moved fast. Everyone else could mimic choreographer Andrea Oberlander’s movements perfectly. How was I, a nondancer, supposed to know that fancy word I couldn’t pronounce was dancer code for stick out a leg?

Everyone at the dance auditions was friendly, though. They’d go over a move with me and either teach it to me or we’d panic together over not knowing it. When I was called on, I was a blur of kicks and turns. I had the beginning of the dance down, but I stumbled through the rest. I was unprepared. I began to wonder why I’d agreed to this.

Needless to say, I did not get called back to learn the second dance.

Then came the wait. There were supposed to be callbacks—another round of auditions to narrow the field—but they didn’t happen. Despars sent out an ominous message: “We’ve seen what we needed to see.”

When the cast of Chicago was announced some days later, there I was: Jonathan Piña-Villanueva, right next to roles for police officer and ensemble. I was in the show, and it wasn’t a joke. It was more than a journalism assignment now. Those in charge of FUHS’s production of Chicago chose me. Thoughts raced through my head.

“I had a role. Maybe I had even taken a role from someone who really wanted it? Maybe there was some kid who’d give the show 100% but didn’t get the chance because I auditioned. Maybe he was a worse singer than me because he hadn’t had five lessons with Melissa Lyons? Maybe he should’ve been chosen instead of me. I’m not that great, and passion beats out experience in my book.” I couldn’t let myself be the weight holding everyone down. I had to fully commit.

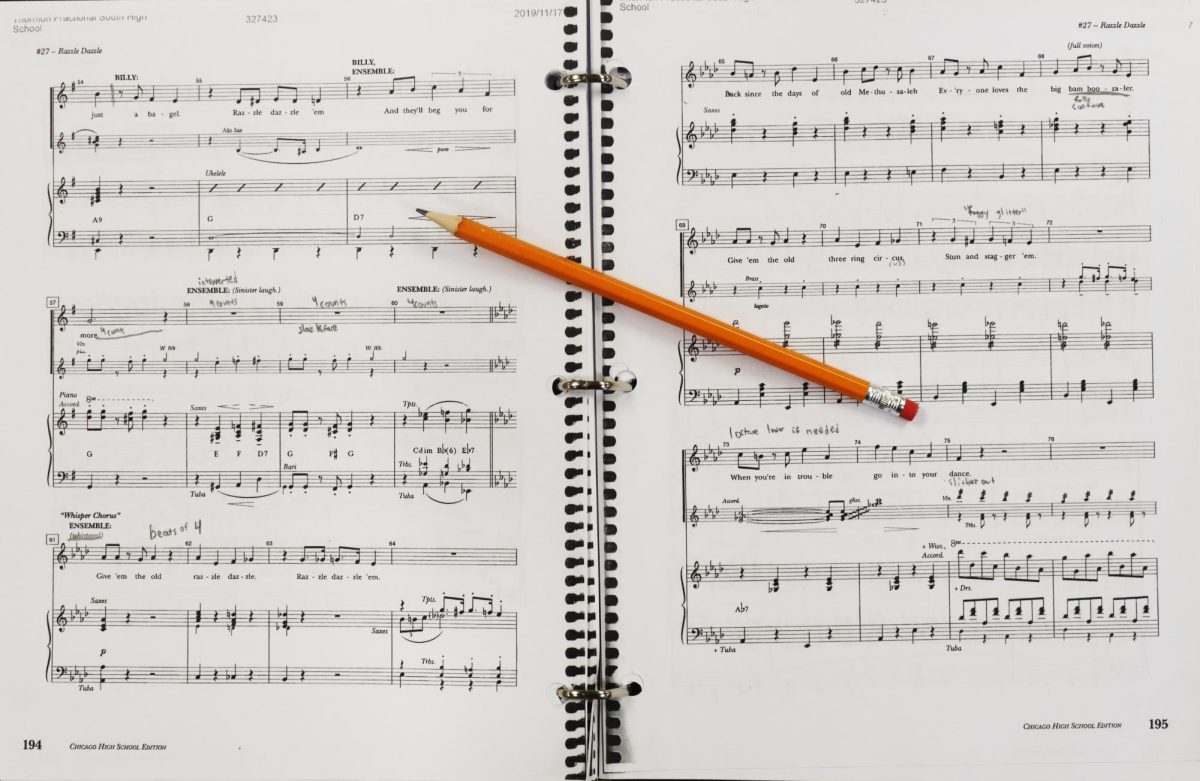

“If you want to live, bring a pencil,” said music director Stacey Kikkawa during our first Chicago readthrough. It was dramatic but understandable. You need to mark up your script. If you don’t take notes, you’ll do it wrong. You also learn from your mistakes. For instance, we started with “All That Jazz,” but I forgot to fill my water bottle. After singing the tenth, “jaaaaazz,” I’d never forget water again.

Choreography for “All That Jazz” was next. I still couldn’t dance, but the slower pace and the fact that we were building on previous moves meant that I could learn, albeit slowly. The featured dancers, on the other hand, would learn entire dances while we ensemble were learning to step right then step left.

Relying on my memory was my best bet. Most of the ensemble, though, already knew that they could dance, and the featured dancers already understood that dance is an art. The differences were clear.

Afterward, we blocked—performed scenes as if we were on stage. Blocking allows the most freedom. As one of several police officers, I wasn’t the focus of any scene, but my fellow officers and I would try to make the stage feel alive.

The Chicago cast performed at the March 8 arts assembly, and that was our first test audience. Chicago was scheduled last. A theater production involves a lot of waiting, too many harsh lights, and a lot of hot, stale air backstage. The fact that more theater people don’t go mad is impressive.

With many of us unused to all this, Assembly A was a bit rough, and the audience was an added stressor. We were awkward. We had to sing out more. Despars gave us a pep talk after, and Assembly B was a significant improvement.

When the assemblies ended, it was clear to everyone that Chicago would be a technical success. The orchestra, the crew, and the choreography were all great. We—the cast—just had to bring it.

In “Cell Block Tango” the last Merry Murderess names her boyfriend’s love interests, one of which is a man. Despars recommended me for that tiny role because he thought I’d be cool with it. He was right. And although I don’t think I look like an Irving, I’m not saying no to a named role.

During both assemblies, my part brought laughter and gasps. Later, friends came up to me and said that it took them a while to realize that I was Irving, the random “Tango” dude.

Theater kids say that tech rehearsals are soul-sucking. Whenever they’d talk about tech rehearsals, they’d emphasize that the day would be achingly slow and that we needed patience more than anything. If anything, this is an understatement.

During the overture, at the beginning of the play, waiters—I was one—walk on stage while the featured dancers perform. Almost immediately, tech called, “Hold!” We started over. “Hold.” Start over. “Hold.” Start over. “Hold.” After four holds, the production moved on. For less than 6 minutes of on-stage time, that overture and “All That Jazz” took an hour. Doing tech for Act 1 took all day.

Waiting in the wings drained me more than I thought it would. If performers could avoid tech rehearsal, they would, but it’s vital to the show. The technical details bring a show together.

I was warned that this week would be rough. Dress rehearsal, sitzprobe (run-through with the orchestra) and finally opening night. Best of all, even less sleep than usual.

I had no idea what to do that first day. There’s no manual for where to go or what to do or how to do something. You either ask or look so lost that someone offers to help.

On the first day I was told to put on stage makeup. After dropping off my stuff, I entered the hair and makeup room and into the chaos that is everyone trying to find their spot and not get in anyone’s way.

I asked around until I got a rundown of what I was supposed to do – foundation, contour, powder. Then I got more help with the details of what goes into putting on makeup. Use a darker shade on the cheeks and jawline, and a brighter shade on the cheekbone. Don’t blend up and down, blend in one direction. When you powder your face, tap, don’t drag.

Costumes were similar in terms of having to learn by word-of-mouth. I had to be told to not warm up in costume and to not touch costumes until someone from the costumes team signed us off. It makes sense when you think about it, but it isn’t something actively present in your head.

The sitzprobe is where the actors and orchestra work together for the first time, but while the orchestra set up everyone else had a dance review of the more complex numbers.

Oberlander and Coach Samantha Monson warned us the previous week that they would have to start cutting people from songs if they didn’t know the choreo. We quickly remembered this fact when Coach Sam walked on stage and started asking for people’s names. It was like seeing the Grim Reaper the way the ensemble held their breath, waiting to see if she would pull them aside.

Somehow I survived the culling, but that only put more pressure on me. “I can’t mess up now; they actually think I can dance!”

After the dance review, the real purpose of the rehearsal began: listening to the orchestra for the first time. Hearing “Overture“ played by a live band was awe-inspiring, and it never lost its impressiveness for the rest of sitzprobe. It felt like read throughs again with everyone sitting down, enjoying themselves listening to the music.

Opening night felt like another dress rehearsal. I knew it was a big day. People were panicking, but I couldn’t register how important it was.

Reality didn’t set in until the cast talk—the pre-show meeting with the entire cast and crew. Depsars, Kikkawa, Oberlander, Coach Sam, and assistant director Jaclyn Stickel gave speeches saying that they were proud of us and how much we put into the show. Everyone teared up when Despars highlighted seniors who went above and beyond. This would be the last show of their high school careers.

Then I remembered how little stake I had in this whole situation. I was on this adventure so that I could write this column. For others, this was their life. I didn’t actually know how they felt because I was an outsider. I had joined the cast; I hadn’t joined the program.

We took our places. Adrenaline surged when I got my first look at the audience. I grabbed my tray and tried to ignore all the people sitting in their seats, but that was pretty much impossible. It came down to this. The audience cheered and clapped after Despars’s opening speech. My mind raced. Could I do this?

The walk from the lobby to the stage was torturous. I couldn’t ignore the audience like I’d planned if I wanted to stay in character and interact with them. My smile hid my pounding heart. I kept pace with the other waiters until reaching the stage where I could hide behind the talented people.

The next day, during the matinee, we didn’t need fake smiles. We were pumped up from the night before. We did it. The show was great. Despars praised us, but made sure to ground us too. After fighting for the rights to the show for 14 years, we helped make his “dream come true.” That was why it was important we kept the energy we did the night before. It was a constant reminder we needed: “Don’t get cocky.”

The matinee’s audience usually isn’t as large as opening night’s, but they reacted to the show as strongly as the opening night’s audience.

The curtain fell, and the audience left. We didn’t. We had another show.

I should’ve known I’d be less enthusiastic during the second show. It was almost a job. Start at noon, warm up, put on your uniform, put on a show, take your break, then do it again. So our energy levels were a hurdle. Putting on a show drains you, and putting on a show right after another show drains you a lot. The theater kids knew how to deal with this. I didn’t.

Thursday’s show took extra effort purely because it was the first show back. Friday’s show felt more natural. I found my rhythm again. I only had to keep it for one more day.

Then: Saturday. The final performance.

Many emotions from opening night returned, except sadness replaced anxiety. In the lobby we waited for our cues, but I could only think about how this would be my last time taking the stage, fixing mocktails and being a bit too loud when someone walked by.

I pushed those feelings aside when the music started, but they returned during intermission. We were halfway done. Just a little longer. The end was in sight. We went back on. Each song put us closer to the final curtain. The finale. And then it was over.

We danced onto the stage, faking smiles. Instead of joy and relief we normally felt during bows, there was sorrow. Sobbing. Tears. Hugs.

I walked to the dressing room to grab my stuff. I changed into my non-Chicago clothes, cracked a few more jokes, and said goodbye to that terrible dressing room.

Being a part of Chicago got me out of my comfort zone and forced me to express myself.

Even while we were still rehearsing, I got nominated to be a part of Fullerton’s Finest. A bunch of senior boys dancing and playing games in front of everyone. Instead of the expected “no way, why would I do that?” I agreed because “why not.” I just couldn’t escape the stage anymore.

Still, theater isn’t for me. I tried it. It doesn’t click with me. I want to have free time. I want to stay in my room.

To be clear, theater requires dedication. It’s not like a club that you sign up for on a whim and only attend meetings when there’s pizza. I thought I understood how much work a production’s cast, crew, and overseers put into a show, but I didn’t really understand until I was in a show myself. It takes a special type of people to balance a full school workload, theater rehearsals, and personal lives. I’m just not that kind of person. I was lucky that my senior-year workload was light enough that I could experiment with it, but had I tried as a junior, I would have missed a ton more assignments and slept even less. And I was in the ensemble. I can’t imagine what it’s like for big roles.

I truly believe that I’m a better person having taken part in a production. It was rough sometimes, but I have no regrets. What’ll stick with me is not the few days that I slacked off but the people I met and the confidence I earned from having helped put on Chicago.