What happens to a student caught using drugs at school?

Let’s say “Bobby,” a junior, gets caught smoking weed at Fullerton Union High School. What happens?

According to assistant principal Leticia Gonzalez, the consequences will depend on if this is Bobby’s first offense. After a conversation with him and his folks, the administrator will assign a three- or five-day suspension. Bobby will sign a behavior contract acknowledging the threat of transfer for a repeat offense. It’s unlikely he will be expelled unless he had an intent to sell or distribute the drugs on campus.

Bobby probably will be given a chance to erase at least part of his crime from his school record by attending three 4-hour workshops hosted by TTC4Success, also known as Leaders in Resiliency, on Saturdays at the La Sierra/La Vista campus. The workshop counselors discuss mental health coping strategies, peer pressure and other drug-related topics.

Gonzalez says the school might make further referrals for mental health counseling. “We try to dig deeper to find supports they need,” said Gonzalez, who tries to help students by applying the “may provide counseling as an alternative to suspension” clause in the Education Code 48900.

The problem for Gonzalez and other school officials is that ultimately they’re in the business of schooling not therapy. The school can send Bobby to a group therapy circle on Saturdays, but he probably needs the level of care for his anxiety and depression that he only can get with health insurance and with parents willing to recognize that it’s the anxiety and depression that are his real problems, not the drugs.

Sure, there are a few free community resource options for mental health care, but the parents who can’t afford health insurance often can’t afford to take off from work to drive Bobby to bi-weekly therapy. Bobby might even need drugs—the type of drugs carefully prescribed and monitored by a physician—but those can be expensive. It’s not surprising that Bobby returns to smoking weed.

Punishing kids for drug use doesn’t work

The Tribe Tribune spoke with drug rehabilitation specialist Patt Ochoa, who has worked with teens for 20 years. He’s not sure to what extent schools can solve the problem.

“It’s the school’s responsibility to know what’s going on, but then the response is punitive because there’s no other option for them,” he said. “But punitive isn’t working. Punitive never will.”

If the school suspends Bobby, he says, “Cool. I didn’t want to go to school anyways.”

“The worst thing we can do for a kid who’s hurting is to lock him up at home,” Ochoa said. “Now he’s by himself because his parents are working. He can do whatever the hell he wants. Now he’ll smoke weed and just be pissed off.”

If schools can’t control drug use, shouldn’t parents be responsible? “It’s their kid. You had one job, raise this kid,” Ochoa said. “How do we hold parents responsible? There’s no real way to.”

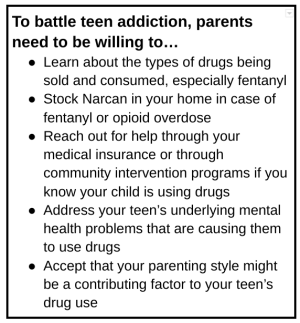

Talking to teens is important, says Ochoa, but parents need to be educated about what drugs are out there, what they look like, how kids are getting them, and why they’re more dangerous than the drugs from 20 years ago.

“I think free drug testing would be a good thing to present to parents,” Ochoa said. “I know the kid doesn’t want to take a drug test and most parents actually don’t want it either. A lot of them don’t really want to know what’s going on.”

But if parents are educated and more involved in the student’s day-to-day life, that can open dialogue and build trust between the two.

Ochoa admits that no matter what he tries to prevent high school drug use, nothing seems to be effective.

“I’ve done everything. Kids who get busted for vaping or smoking weed go to drug classes. We do all kinds of groups, we do all kinds of education. I take panels into high schools, I can bring kids to speak to you guys about their experience with drugs and alcohol, right? It doesn’t seem to be effective.”

He believes that if parents aren’t educated and don’t create a positive family unit that kids will continue to fall into drug use to cope with stress and depression.

“Okay, let’s get in front of the PTA, get in front of the parents, talk to them,” he says. “Send out, you know, hundreds and hundreds of info sheets to get educated on fentanyl, get educated on Narcan. I think every family should have Narcan at home. Because kids are dying of fentanyl.”

Ochoa says if parents don’t know how to administer Narcan, they risk watching their child die from an accidental overdose.

“But parents don’t wanna believe that their kids are smoking weed at home. They turn a blind eye. My kid’s never gonna do that,” he said. “Until someone’s dead. And then you have weed laced with opiates. And suddenly you need it.”

JADE: Program requires parent participation

But Ochoa says he does see some progress when schools partner with outside organizations like the California Youth Services (CYS).

Instead of serving suspensions at home, students in the Los Alamitos District go to the district office for three days, 8 a.m.-2:30 p.m. where they listen to drug intervention specialists from CYS and participate in workshop discussions.

CYS also provides the Juvenile Alcohol and Drug Education program (JADE), which allows students to clear their drug charge from their record if they and their parents attend a 10-hour class over two evenings. That’s right. Parents in Los Alamitos, Huntington Beach, Irvine and Tustin have to go to drug school with their kids for five hours one night and five hours another night the following week, from 5-10 p.m.

Students take a drug test and are required to test again in two weeks if they’ve been using nicotine or test in 45 days if they’ve been using THC (Cannabis with Tetrahydrocannabinol). If they test positive, they are required to attend an outpatient treatment facility for a higher level of care.

Most of the workshop hosts sessions and guest speakers for parents in a separate room, but a few presentations are intended for the family. After the program, parents can purchase additional top-grade 14-Panel drug tests that screen for fentanyl, opiates, THC and other drugs. Parents can also buy cheaper versions at drug stores or on Amazon.

Emma Seavey, the program manager at CYS for Alternative to Suspension Programs, told the Tribe Tribune in a phone interview that drug abuse often persists because of ignorance regarding drugs.

“Students think THC and nicotine are harmless ways to feel better because of what they hear on television or through music,” Seavey said. “Because THC is legal for adults in California, we’re hearing that more and more from students. They say, ‘I’m taking this for anxiety, I’m taking that for depression’ when in fact the THC makes anxiety worse.”

Certainly, parents aren’t happy about having to go to 10 hours of JADE because of their teen’s drug use, says Seavey, but one message is becoming clearer: fentanyl is making parenting even scarier.

“We’re at a point in history when there really is no safe drug experimentation,” Seavey said. “We’ve tested students’ nicotine vapes and counterfeit carts and they’ve come out positive for fentanyl. It’s completely rampant in Orange County right now.”

Fullerton district tries to educate parents, but it’s a short reach

Our school district is trying to help parents, too. The FJUHSD hosted a parent workshop at Sunny Hills High School in October. The Fullerton Police Department and campus resource officers covered topics ranging from online predators to bullying to drug use. According to Allen Whitten, director of student support services, only about 50 people attended, but district officials posted a video of the workshop.

“Those who have attended have been very appreciative, but obviously we would like to reach a larger audience,” Whitten said. “The world is changing at a rapid pace. The more we can support each other, the safer our kids will be.”

Whitten says the district hopes to partner with the Buena Park Police Department to host a fentanyl workshop before the end of the school year.

The district also invited the OC Health Care Agency to host a fentanyl awareness workshop in the FUHS Little Theater on Jan. 26. The event included a panel of parents whose children died from overdose. About 200 parents attended and were receptive and grateful for the information presented. (See full story here.)

What now?

The Tribe Tribune staff has been investigating drug use for nearly three months. We even interviewed 17 teens who regularly use drugs ranging from a few vaping puffs here and there to consuming entire Xanax bars daily. Their attitudes ranged from “I’m fine; my parents are cool with it” to “I want to stop, but when my friends have stuff, it’s hard to say no.” A particularly sad interviewee confessed to stealing money from his grandparents to support his marijuana habit.

The staff was also alarmed to learn that many middle school and even elementary school kids are already regular drug users.

FUHS school nurse Kristina Smith admitted that the “magnitude of the problem is so extensive” that it’s hard to know where to begin. She was, however, very supportive of the Tribe Tribune for using our “platform of journalism to work toward finding solutions.” Beyond that, Smith and other professionals agree that it takes many interventions—mental health care, family counseling and “early, age-appropriate health education.”

Ultimately, what students need is support from their parents in a way that makes treatment more important than the penalty. Many students recognize the problem but fear that their parents will reprimand them, or, worse, be ashamed of them. It is imperative, however, that parents cast aside their anger and disappointment and prioritize the health of their children.