Alum increases head injury epidemic awareness

October 6, 2022

Top FUHS athlete. Former FUHS teacher. Passionate filmmaker.

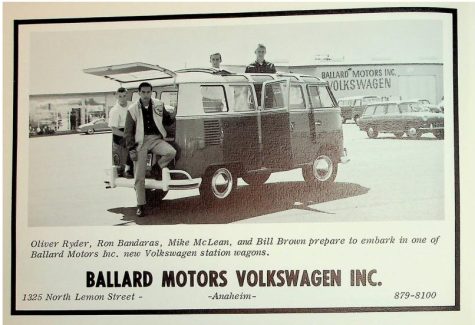

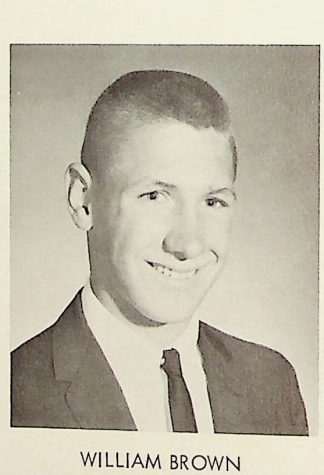

Bill Brown, class of 1964, has a resume that makes him the perfect inductee for this year’s Fullerton High School’s Wall of Fame. Brown is especially praiseworthy for his 2008 documentary Hidden Epidemic that showcases the seriousness of post-concussion syndrome.

His film matters because there was a time when concussions were ignored, like when Brown was a freshman swimmer at FUHS in 1960. Brown remembers wanting to set up on the other side of the pool so his coach could time him. He was hurrying on the pool deck when he slipped.

“I went up and landed on my tailbone,” Brown said. “The energy then went up my spine. Back in those days, it was just one of those, ‘Oh, come on, shake it off.’”

But Brown couldn’t shake it off.

It usually takes 10–14 days to recover from a concussion, but Brown’s headaches, memory loss, and mood swings persisted not for days or weeks but for years.

Brown said that he could be exposed to something that he truly cared about, but the injury would cloud the memory. Brown searched for an answer to his condition.

“There’s a lot of what I would call free floating anxiety and non-specific depression. You know, ‘I feel anxious but I’m not. I’m worried and I don’t know why,’” Brown said. “I made it my business to spend a lot of time during high school in the Fullerton public library. I was desperate and hungry for answers, and there were none.”

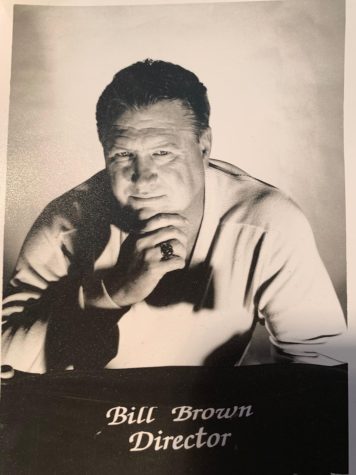

That search for answers would eventually culminate in Brown writing and directing Hidden Epidemic that documents the concussion of a cheerleader. By combining narrative with doctor interviews, Brown educates his audience about how post-concussion syndrome affects academics, relationships and daily life.

Although Brown felt the weight of post-concussion syndrome in his own life, he still remained one of the most successful athletes in FUHS history. Brown went undefeated in swimming in 1964 and set a CIF record in the 100 freestyle. Brown earned All-American honors for water polo and swim his senior year, and Fullerton won the CIF Championship in 1963 and 1964.

He also helped the Trojans earn a NCAA Swim Championship in 1967 while he studied Film/Television Production at USC. He is a founding member of the USC Cinema/Television Alumni Association.

With his love for research and education, Brown became a high school English, history and psychology teacher. He taught at La Habra and Troy before coming to Fullerton in 1990.

Campus supervisor Rose King says that Brown “did so much for the kids.” The student’s experience at FUHS was his number one priority.

“I helped Bill and we would host parties like a Luau,” King said. “Students could go swimming, and we would have guys [twirling fire torches] performing. We’d set up the volleyball net. We just did stuff for the kids. It was fun.”

King says she remembers how Brown would lead campus tours, educating students on FUHS history.

“He told them everything. The oldest tree. This was dedicated to this person. And this bench over here was dedicated to this person,” King said. “I went on the tour. We used to be able to go down in the catacombs. And he would take his classes down there. So I would always go, ‘I wanna go!’”

Although he loved history, Brown said psychology was his favorite subject. He tried to make his class interactive and dove deeper into the “why?”

“I was kind of copying a format that came from Harvard designed to allow the learner to understand their world better, who they are, and who other people are,” Brown said. “We didn’t spend time memorizing when and where Sigmund Freud was born. It allowed us to go deeper into why. Why did this happen? Why do you think somebody feels that way?”

Brown took a two-year break from teaching to direct the film Dream Rider (1993). He wrote the screenplay based on the true story of Bruce Jennings whose leg was amputated after a motorcycle accident in 1970 when Jennings was a senior at Troy High School.

Brown’s fascination with psychology and “why” compelled him to write the film which co-starred James Earl Jones as a fictional mentor to the Jennings character.

“Bruce Jennings knew my sister who went to high school with him,” Brown said. “He would come over to our house and play basketball next door. I was learning more about the guy and I thought, ‘I think there’s a real story here about healing, about getting through tough times.’”

The film focuses on Jennings’ cross-country bicycle trip six years after

his leg was amputated. Jennings, who also suffered from multiple head injuries, took up cycling while recovering and became the first one-legged person to cycle across the United States. Through making the film, Brown connected the dots of his own head injury complications.

“I never knew what my injury was until 1990 when I was making a movie about a Fullerton boy who got a concussion and had post-concussion syndrome,” Brown said. “I made the movie about Bruce Jennings, how he healed, and that’s when I started learning about post-concussion syndrome. That’s when I figured out what probably happened to me.”

From his own experiences, Brown knew a person can’t just shake off depression that sometimes comes with post-concussion syndrome. And despite fighting a constant battle, Jennings, at age 34, died from a drug-alcohol combination that was likely suicide.

After retiring from FUHS in 2009, Brown continued to spread awareness about post-concussion syndrome and suicide prevention. Brown has lectured about PCS at schools such as the Gonzaga Law and University of Washington and has developed a suicide prevention curriculum for schools in the Northwest.

“It’s one thing to say that Bruce Jennings committed suicide, and he died on this date. It’s another to learn what the probable causation was and why,” Brown said. “I’d learned about Bruce making that movie and three years later when [my son] Billy got his concussion, I was up to speed immediately. I was able to find the right kind of doctors that could treat him in the right way. There’s more I need to learn here. And whenever I learn, I can share.”

Brown, along with his son Billy Brown, Jr., will be honored at a homecoming ceremony on Oct. 7. There will be plaques honoring them both and will be displayed in the front office.