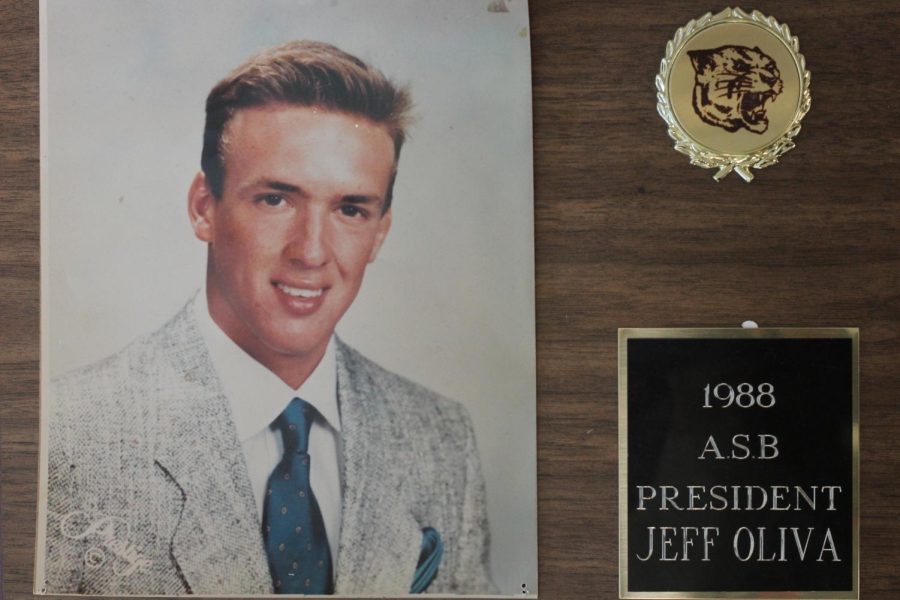

Jeff Oliva has been asked some tough questions in his career. As a computer science and chemistry teacher, Oliva often explains complicated material. But when a student asked, “What’s the hardest thing you’ve ever done?” Oliva had an easy answer: “Quitting nicotine.”

Initial Exposures

Oliva says his grandmother’s excessive smoking exposed him to nicotine early. “I saw how she was physically,” Oliva said. “It consumed her. She had cigarettes and just piles of cigarette butts at her house. I hated going to the house because it smelled.”

During high school, Oliva worked as a landscaper on a golf course. Work was long, difficult, and usually done alone. One day he was tasked with watering a large fairway by himself. His friends and fellow workers chewed tobacco. Curious, Oliva tried it.

“It was a friend who had his bag of Red Man, a brand of chew. I think the very first thing I tried was that Red Man.”

His first use wasn’t enjoyable.

“It was like a combination of a drug high, but also nausea,” he said. “You know something’s happening to your body. It felt like the world was spinning.” Oliva finished high school without further nicotine use.

At USC, Oliva’s roommate smoked, so Oliva had easy access to cigarettes. “Because of the different social scenes,” Oliva said, “I think I probably tried smoking a little bit more often. It was just a thing around campus.”

Oliva’s post-college girlfriend also smoked. Although Oliva was never an avid smoker, he became more comfortable with it.

Addiction Road

During his last years of college, Oliva began coaching high school varsity football. He remained in contact with his high school buddies who dipped, but his new friends and some coaches dipped tobacco, too. He started chewing tobacco more often. He wasn’t hooked, but the culture around him made it feel natural.

Oliva’s younger brother, Jonathan, was on the football team. Oliva’s use up to that point was seldom enough that his family was unaware of it. Jonathan was the first person outside Jeff’s friend groups to see him regularly chew tobacco.

When Jonathan—now Dr. Oliva, a physician—entered college, he wrote Jeff a letter. Knowing his brother’s interest in science, he guessed it would break down scientifically the hazards of his continued use.

“I knew at any given time a gene in a cell could be exposed to a carcinogen and make the first cell cancerous,” Oliva said. “I knew prolonged use might cause emphysema like it did to my grandmother.”

“By that time, I was in denial that I was addicted,” Oliva said. “I was like, ‘I know it could be bad, but I don’t want to hear it from you, little bro.’”

Oliva never read the letter. He was aware of nicotine’s effects and didn’t want a constant reminder. Almost 25 years after deleting the letter, he wishes now that he could. He thinks that if he had read it, he would have quit earlier. “I knew he cared. I knew what he was saying,” he said. “I just never read the exact words.”

Oliva coached for three years and chewed tobacco at every practice; he was still dipping when he became a teacher in 1996. In his first year of teaching, he realized his addiction. The principal walked into Oliva’s class while Oliva was chewing tobacco. His students had alerted the principal.

“I flat-out lied to that principal,” Oliva said. “I saw him walk through the door, and I turned my back to him. I may have even removed it and had it in my hand while I talked to him. It’s illegal. Looking back on it, I can’t believe the stuff I used to do because of the nicotine addiction.”

After that, Oliva was more discreet. He would satisfy his addiction during breaks and lunch, cleaning himself up before students returned. When out with friends, he would slip away to chew.

Trying to Quit

Oliva wasn’t properly motivated to quit the first few times he tried. From 2002 to 2005, his first three years at Fullerton, he wanted to better his health and cut out nicotine completely.

“I was counting the days [since I’d stopped], and it felt good because you’ll have three, four days under your belt,” he said about his first attempts, “but then withdrawal symptoms start. They’re real. And they’re painful. So I resumed using.”

After several failed attempts, Oliva started using nicotine gum and patches to lower his dependence. “I realized I could at least wean myself off the habit and—paying attention to doses—reduce the amount of chemicals in my body in a measured, scientific way.”

Oliva finally quit when, as a new father, he was denied affordable life insurance. His first daughter, Beilen, was born in February of 2011.

“I’m a dad now,” he said. “I gotta take care of my kids. I can’t just take care of myself.”

One of his first responsibilities as a new parent was providing life insurance, which he didn’t have. Oliva’s life insurance would cost five times that of a nonsmoker’s.

He also wanted to be healthy to see his daughter grow up.

“Every dollar I spent would’ve been money coming from my daughter,” Oliva said. “I did not want to pay that rate. It was a big motivation to help me quit.”

In order to qualify for a reduced rate, Oliva needed to be nicotine-free for one year. The withdrawal symptoms Oliva faced were the same as before, but now he had motivation.

“The pain goes away. You’re able to get some sleep,” he said, discussing weaning himself off his addiction. “Weeks become months, and then it becomes so long you don’t think about it anymore.”

Current Thoughts

Looking back, Oliva realizes that his very first use was the most influential. Were he around different people, it’s possible he wouldn’t’ve gotten addicted at all. Curiosity, though, can be as strong as addiction. Oliva encourages students to seek help for addiction early. Quitting is not only healthy, but it also saves money— over the course of years even a few dollars a day spent on an addiction adds up. Further, smoking can interfere with relationships.

As smoking culture changes, Oliva finds he has fewer opportunities to share his experience. With cigarettes increasingly uncommon, there are fewer signs that a student’s an addict.

“If someone reads this story and quits,” said Oliva, “then sharing this story is worth it.”

Sophomore Samantha Torres contributed to this story.