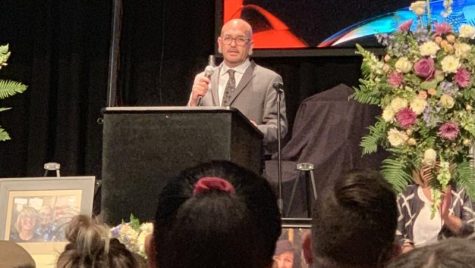

Drug rehabilitation specialist Patt Ochoa educates teens about the dangers of counterfeit drugs, especially knock-off Xanax bars that are often cut with fentanyl, a cheap synthetic opioid that is 100 times more potent than morphine.

But no matter how much he fights to keep people alive, Ochoa sees fentanyl winning.

“I just had three kids I worked with last month—17 years old—smoking weed. It was laced with fentanyl. Dead,” Ochoa said. “Fentanyl in a dab pen killed three people.”

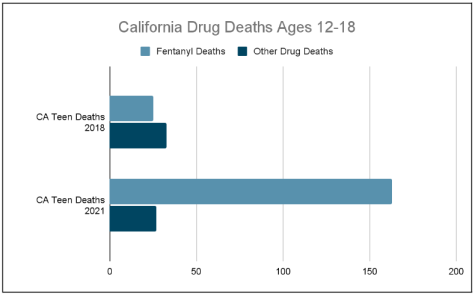

Fentanyl is killing young people in California at an alarming rate. According to the CDC, 25 Californians ages 12–18 were killed by fentanyl in 2018. By 2021, the number had jumped to 163.

Some are dying because they don’t realize a drug they bought—often through social media—contains a fatal amount of fentanyl. Others willingly ingest the drug because it is inexpensive but potent.

Threat of death not a deterrent

Ochoa, who is the program director for Liberty House Recovery, a comprehensive drug/alcohol medical detox facility, explains that drug dealers, unfortunately, are not deterred by people dying.

“The heroin addict or the opiate addict wants to take enough drugs that they almost die,” he said. “He wants to get near the point of death.”

The addict realizes that not everyone will die from the same batch of fentanyl-laced drugs and is willing to risk not receiving a lethal dose.

“When someone dies, the addict thinks, ‘That’s the drug I want because I want that near death experience. So the dealer that sells drugs cut with fentanyl, where you think he’s lost business, now he has a line of 10 people wanting his drug. Business increases. So for the dealer, it’s a win for him to put in even more fentanyl to increase the level of intensity.”

Ochoa understands this twisted logic not only because he’s a drug counselor but because he’s a recovering addict. When the teens he counsels say, “You don’t understand,” Ochoa is not afraid to share his own story of addiction and recovery. His openness is one tool for building trust.

Childhood drug use

“My first time smoking weed I was 11. They were older and they handed me a joint,” he said. “I couldn’t say no to these older kids. I was smoking weed just about every day by the time I was in ninth grade.”

Ochoa says his mother did her best as a single parent, but admits he took advantage of the lack of supervision. When he was born, Ochoa’s mother was an alcoholic, but she got sober before his first birthday. She remained sober until her death in 2019.

Ochoa says his education basically stopped freshman year. “I came to school, but it was more for the party and for meeting a girl,” said Ochoa, who attended Capistrano Valley High School. “At 17 my mom kicked me out of the house. She said, ‘You can live here and be sober or go and get loaded, but you need to make a choice.’ And so I chose to leave at 17.”

Ochoa used marijuana and “all sorts of narcotics” in high school. “I smoked weed every day, little amounts, a gram, two grams. By the time I was a senior, I was buying quarter pounds of weed and selling it,” said Ochoa, who then moved onto harder drugs.

Addiction at its worst

By the time he was 27, he was living on Skid Row in Los Angeles using heroin, methamphetamine, crack cocaine and alcohol every day.

“[In high school] I could break into cars and steal stereos. I could break into houses and steal things to provide for my habit. By the time I was living on Skid Row, I was prostituting myself to get drugs,” said Ochoa, who was consumed by “self hate, shame and guilt.”

“I was 98 pounds and hadn’t showered in six months. Yeah, so that’s the condition I was in when I got sober at 27,” said Ochoa, now age 47. He called his mom who helped him quit methamphetamine, heroin, crack cocaine and alcohol cold turkey.

“I just sat in bed and just, like, shook for 21 days. I couldn’t sleep for 26 days. I could barely eat for eight days. I was absolutely terrified and alone. I was suicidal, depressed. The anxiety was just so incredible.”

A calling to help others

Two years later, Ochoa started working in the rehabilitation field at a sober high school in San Juan Capistrano called Coastal Mountain Youth Academy (CMYA) designed for teens who can’t stay sober in public high school. CMYA is an educational and therapeutic day program for “at promise” (rather than “at risk”) youth. The program includes wilderness training, team building, drug counselors, therapists and small class sizes.

“I don’t think all kids are going to be successful in a public school. Some need education outside of the public school system. They do better in a six-person classroom compared to a class of 35 where they’re lost,” said Ochoa, who then went on to work at Newport Academy, a residential treatment center where he built a recovery component to help kids get sober.

Some teens need a 90-day program for the best chance at staying clean long-term. While health insurance can reduce the cost, the best programs can cost as much as $40,000 a month.

“Rehab is super expensive. If you have insurance, they may cover a third of it, and then the family’s financially responsible for the other two thirds,” he said. “Families are struggling just to provide a house, to provide food. So then only the wealthy can get services. And if you’re low income, I mean there’s no low income rehab beds for adolescents in Orange County right now. Zero. That’s a problem.”

Ochoa opened a transitional living home for adolescents called Sustain Recovery in 2015. He also developed 11:11 Coaching, a program to mentor adolescents and families with substance abuse and mental health issues.

Even for those with access to drug rehab and other interventions, Ochoa says it takes a lot of strength to get help. “There’s a stigma around being sober because, unfortunately, drinking and doing drugs is the norm,” he says.

“I’m in the industry of helping people that don’t want to be helped,” said Ochoa, who explained that the brain convinces a drug user that continuing the drug is the best—and the only—path.

“Let’s say I’m a teen using drugs or alcohol to treat my depression and someone comes along and takes away my drugs. The only solution I know has been removed. Addiction being powerful, I’m gonna do everything I can to get that back.”

“Getting clean takes time. Why do that when weed gives me relief immediately? I don’t wanna do the work to get that. Why would you?” he said. “Of course, drugs don’t make sense logically to someone who’s clean. But when you’re in, it makes all the sense in the world.”

Need a clean and sober culture

One approach to living sober in a drug-using world is to create safe spaces for sobriety. Ochoa created a non-profit called Harmonium Inc., that sets up a clean-and-sober tent at about 35 music festivals across the country.

What teens need most, Ochoa says, are clean and sober peers whom they trust. School culture needs to change to provide peer support in addition to counselors and other interventions. Ochoa says that the majority of high schoolers have friends who are struggling with addiction or mental health.

“We’re all trying to talk to them, but some young people struggle to help. They feel powerless because they don’t know what to do,” he said. “The best thing we can do for our friends is be there to talk about what’s really going on.”

Teens lack coping skills

Despite his best efforts, Ochoa says his job is getting tougher, especially with fentanyl making drug use even more dangerous. Experts testifying at a senate hearing on Feb. 15 reported that 410 million doses of fentanyl coming through Mexico were seized by Customs and Border Protection in the last 12 months. Experts also reported that fentanyl poisoning and overdose is now the leading cause of death for Americans ages 18 to 45.

And it’s not just fentanyl that worries Ochoa.

“Vapes, too. Nicotine’s way more physically addictive,” Ochoa said. “A kid thinks he has to hit the vape to calm down when nicotine actually increases anxiety. It’s the most backwards thing ever. How many times do you hit a vape in an hour versus cigarettes? It’s nonstop.”

Teens who take pills, smoke weed and vape think they’re managing their mental health problems when, in fact, they’re making things worse. “Drugs are really just a symptom of mental health problems,” Ochoa said. “The problem is mental health; drugs and vape are just symptoms.”

What might have started out as something they do with their friends evolves into self-treatment for mental health problems.

“They say, ‘That hit of weed I took made me feel better. I’m sad today, so I’m gonna smoke again.’ Now they’re realizing their issues at home, which they’ve had all along. But they think, ‘When I smoke weed, I don’t tend to feel sad,’” Ochoa said. So then they’re smoking maybe subconsciously to take care of that stress at home.”

Teens lack coping skills. “But remove the weed and you see more anxiety, depression and low self-esteem,” he says. “Those with anxiety and depression are worse than before they were smoking.”

Most teens aren’t looking to stop. Maybe one in 10 teens know they need help. “But that kid is never gonna be like, yeah, let’s get help because his coping mechanism is weed. “If the kid is already smoking weed, his solution is ‘Hey, I’ve got my weed. Why try and fix a problem when I have a solution?’”

Today’s drugs are stronger than ever

Ochoa says that alcohol, nicotine and THC aren’t necessarily gateways to more drug use. Instead society’s acceptance of drug use leads to more drug use. Especially now that marijuana is legal in California, people have given up on staying clean.

Legalized marijuana comes with issues, too. Even if it’s not laced with fentanyl, it is stronger than weed from several years ago.

Ochoa says that high concentrations of THC available in “dab carts,” a cartridge full of a waxy concentrate, makes a big difference in teenage marijuana dependence.

“We didn’t see the 90% THC levels you’re getting at the dispensaries today, it was more like 25%,” Ochoa said. “Because smoking is progressive, I could smoke one hit of good weed. Two years later, I gotta get an eighth to myself. You need more to get the feeling, so you start selling drugs in order to provide for your own use.”

Ochoa said he is starting to see more adolescents becoming addicted early on. Teens are building up a quick tolerance for drugs which makes them seek even stronger drugs. “Weed no longer working for me? I take a Xanax. It gives me relief in a much more intense way than the weed. Now we’re addicted to opiates,” he said.

Parents need to do the work

When a teen is referred for rehab or drug counseling, Ochoa says he first assesses them physically, mentally and emotionally. He looks at the types of drugs the teen has been using, their mental health history, suicide assessment and the family’s medical and drug use history.

Possible treatments include individual therapy, group therapy and outpatient care. In some cases, residential treatment or a long-term boarding school might be the best approach. ”If a kid doesn’t have a supportive family system, then we give the family education,” Ochoa said.

If a child is using drugs then the entire family needs to work on solving the problem.

“A lot of times the family wants to send the kid to rehab. [They say,] ‘Here, fix him,’ but they don’t want to do any of the work. They don’t want to look at the family system,” Ochoa said. “Maybe dad’s working so much and mom’s the only one at home. The kid wants a father figure. A lot of times we see that dad doesn’t know how to be emotionally available for his kids.”

Ochoa says that very few adolescents will come through rehab and be sober for the rest of their lives. He thinks that a success story isn’t a 30-year sobriety chip, but a teenager who can rebuild trust with their family, improve their grades and recover their mental health.

Parents need to be open and honest.

“The parents don’t want to talk about their problems within the family system. They want the kid to do that. And what I believe as a counselor in this field is that it’s a family deal. We need to restructure the family.”