Journalists should be objective, and journalists shouldn’t get attached to their subjects, but journalists who cover tragedies like mass shootings can’t remain objective and do get attached. This paradox led alumni Jesús Ayala (class of ’98) to research the effect of mass shootings on the journalists who cover them.

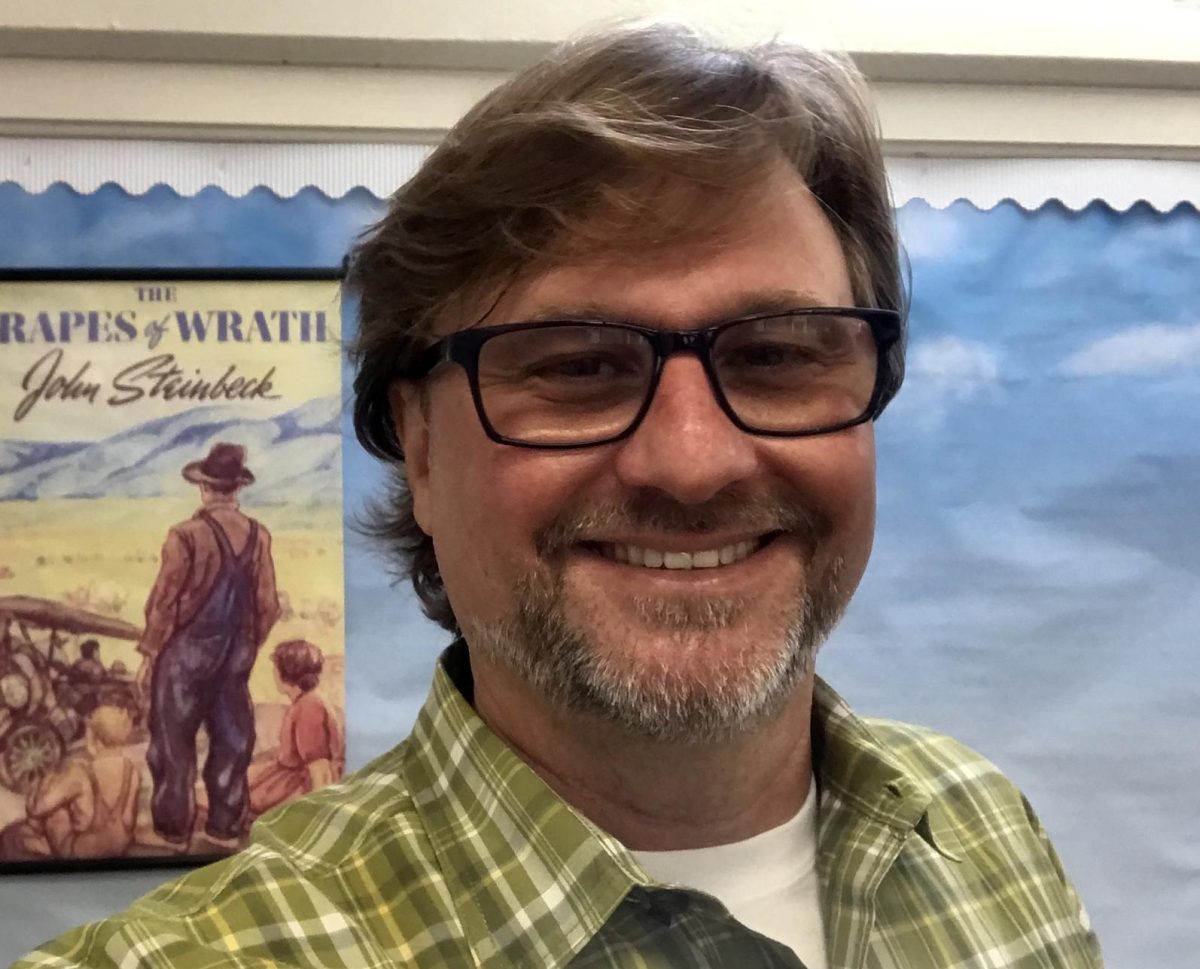

With over 20 years of journalism experience, Ayala has covered everything from Barack Obama’s 2008 presidential campaign to Hurricane Katrina to Venezuelan political protests. Ayala’s won five Emmys and seven Edward R. Murrow Awards. Because of his journalism and teaching expertise, Ayala will be added to the FUHS Wall of Fame during an award ceremony on Oct. 25 at 5 p.m.

Ayala, a professor at CSU Long Beach, prepares a new generation of journalists for the psychological impact of broadcast journalism. “[Broadcast journalism] is a pressure cooker,” Ayala said. “If you don’t process, it’s going to boil and that will not be pretty.”

Ayala was approached in 2022 by Raya Torres, who was his student at Cal State Long Beach, about her senior thesis. Torres wanted to combine her interest in psychology with her interest in journalism. Ayala, who had covered catastrophes to such a degree that he’d developed post-traumatic stress disorder, still needed a research project to get tenure. According to Torres, Ayala and she were a “match made in heaven.” The two researched the effects of the 2022 Uvalde, TX, shooting, but instead of focusing on the survivors or the victims, they focused on the journalists who covered the event.

Ayala and Torres traveled to Uvalde, Texas to conduct their research. The two interviewed 10 journalists who had covered the shooting.

“In an effort to remain impartial and unbiased, [journalists] end up becoming somewhat robotic because they’ve always been told not to acknowledge emotion,” Ayala said. “They leave emotion out of it. So then what ends up happening is that they go through their careers trying to stay impartial and trying to control emotion.”

The research at Uvalde inspired Ayala to teach his students what he calls trauma-informed reporting.

“You have to recognize that, as a journalist, you’re going to cover traumatic stories,” Ayala said. “You have to learn how to take care of yourself.”

Ayala also teaches about how to properly and respectfully interview victims of tragedy.

“The Society of Professional Journalists’s code of conduct says that journalists are supposed to minimize harm,” he said. “If you’re going to be dealing with trauma victims, you have to be trained how to ask questions.”

After completing her thesis, Torres took a position with 13 News in Arizona. She had to apply what Ayala taught her on her first broadcast assignment which was covering a shooting at the University of Arizona. Torres immediately called Ayala. He reminded her of what it was like when they were in Uvalde. He reassured her, saying, “You know what reporting on these stories can do to you, so you’re gonna be okay.”

She added: “That felt very comforting. I definitely feel like a better reporter because I’m able to empathize with their experiences and I’m able to understand them more because of the work I did with Jesús.”

Ayala is the founder of the Mindful Newsroom and frequently speaks about the importance of mental health in journalism and how to avoid burnout. Currently, he’s producing Reporting from Uvalde, a documentary that chronicles the role of journalists at the scenes of mass shootings. Ayala views journalists as first responders. With the documentary, he hopes to explore the physical and emotional trauma that journalists are exposed to while reporting from the frontlines.

Before working at CSULB, CSU Fullerton Communications Professor Jason Shepard hired Ayala to teach part-time. One of Ayala’s first classes was how to report on the entertainment industry.

“[Ayala] tried to go beyond the more superficial aspects of covering a story,” Shepard said. “He used his background as a producer to teach students how to find story angles that would be relevant to a wider audience but also tailored to each student’s interests.”

Ayala taught a special class on border reporting and took students on trips to the border, navigating the mountain of red tape alongside his students.

“He was so passionate about giving students frontline fieldwork and real-world experiences,” Shepard said. “They’ll remember that forever.”

Shepard noted that Ayala’s students love being in his classes because he forges connections with them as individuals and makes them feel seen.

His former student Torres agrees: “Of all the talented professors I’ve had, no one has left a more lasting impact than Jesús. I don’t think that I would’ve had the strength to take risks and be the journalist I am today if it wasn’t for his guidance.”

College

Ayala was accepted into Yale, Stanford, and UC Berkeley. He chose Berkeley and a double major in political science and ethnic studies, hoping to become a lawyer.

During his third year of college, Ayala experienced a change of heart.

“I realized I didn’t want to become a lawyer, but I started to feel a little lost,” Ayala said. “In high school, I’d been so focused, ambitious and determined.”

A required mass communications class became a blessing in disguise.

“I had wanted to be a lawyer to make a difference,” Ayala said. “It had never occurred to me that I could make a difference by shaping public opinion through journalism.”

Ayala got his undergraduate degree at Berkeley. After completing an internship in Washington, DC, Ayala studied at USC’s Annenberg School of Journalism. It was at the Annenberg School that he earned a Master’s degree in journalism and landed a job as a producer with ABC News.

Ayala recognizes that having a political science degree was a big help, especially when he was covering former president Barack Obama’s 2008 campaign.

“It was exhilarating to actually be on the road with the first African-American president,” Ayala said, “and, honestly, in those moments, what really helped me was understanding the electoral college.”

High School

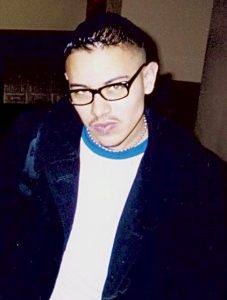

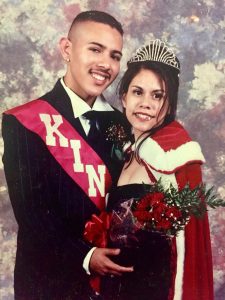

In his senior year, Ayala decided to run for ASB president. Ayala didn’t see himself as the type of person to win; he was openly gay and made no effort to hide it. He was surprised when he was elected ASB President, lip ring and all.

“At a time when most people are trying to fit in, I was not about fitting in,” Ayala said. “I think that resonated with my classmates. I was unapologetic about it, and I was not afraid to be me.”

When it came time for him to write a speech for graduation, Ayala was faced with opposition from the graduation committee made up of teachers and administrators.

“They wanted to censor my speech and prevent me from speaking,” Ayala said. “I had planned to talk broadly about themes like toxic masculinity and expectations in Latino households, and say that no one should ever conform to these expectations that are really not serving us.”

This was viewed as a coming-out speech by the committee. To Ayala, his speech was anything but controversial. He was unabashedly himself, but wanted his speech to shed light on the issues that he faced personally.

On the graduation committee was English teacher Genni Klein, who defended Ayala’s choice to discuss toxic masculinity in his speech. She threatened to take her coworkers’ objections to the district if they barred Ayala from speaking.

“Orange County was very conservative back then,” Ayala said. “[Klein] fought hard for me, and I will always love that.”

For Ayala, being inducted into the Wall of Fame is a full-circle moment. When he was applying to college, he couldn’t afford a typewriter to complete his applications. For four months, he stayed after school and used school secretary Fabiola Lodges’s typewriter. One day, he had writer’s block.

The desk he was borrowing overlooked the FUHS Wall of Fame that celebrates successful FUHS graduates. He looked at the Wall of Fame faces for inspiration but was ultimately disappointed.

“It was the opposite of inspiring,” Ayala said. “I remember the more I stared at the Wall, the more inferior I felt because I was not represented.” In 1998, most of the graduates on the Wall of Fame were white.

Ayala made a promise to himself: “I said, ‘I’m going to be on that wall one day because representation matters.’”

This week he fulfills that promise he made to himself. But it’s also a message that he’s been delivering to his students for years.

“Everyone’s superpower is their authenticity. People can always tell when you’re faking it,” Ayala said. “Once you’re just yourself, unapologetically, students respect that.”