Although I’m Korean, I grew up in a typical American evangelical, predominantly white church. For years, I endured subtle racism and misogyny. When some boys found out I attended a march for gun control, they chased me out of the building with an NRA hat, yelling at me to put it on.

But when I got to high school, I found an outlet: my freshman English class. It was an environment where I could finally speak, and I overused and abused this new privilege.

The day after Donald Trump’s election, some students rejoiced and others cried. I was outraged. I ranted in class discussions. I seized every opportunity to mock conservatives. In one essay, I even called Trump “President Donald Duck.”

In all honesty, expressing myself in these ways made me feel strong, intelligent, powerful— qualities I’d never felt before.

Fortunately, my classmates didn’t retaliate against me and my soapbox. At first I thought it was out of kindness. But now, I wonder, was it out of fear?

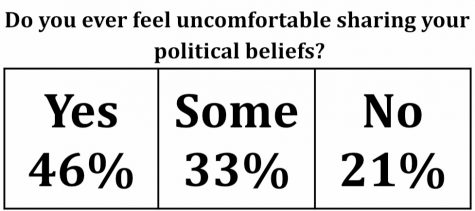

A recent Tribe Tribune survey asked 144 FUHS seniors if they ever feel uncomfortable sharing their political beliefs. 46% said yes.

“Being a conservative in a leftist school is probably the toughest thing a person has to go through,” senior Kameryn Bergeron said. “I feel like anything I say I will be attacked, bullied, or shut down.”

Government teacher Katy Wren says because of feelings like this, her lesson-planning style has changed.

“Right now, it’s hard to teach government,” Wren said. “I have to take into account, is someone going to be upset? I didn’t have to do this in the past, five years ago.”

Similarly, government teacher Aaron Vandenburgh says he stopped including political debates in his curriculum.

“A year or two ago, that got pretty ugly,” Vandenburgh said. “A constructive activity is now destructive.”

While it may be beneficial to avoid controversy, Wren also says that attempting to prevent toxic debate stifles the development of important life skills, especially that of civil discussion.

“You’re going to go out into the wild and talk to people with all different sorts of thoughts,” Wren said. “I think about it all the time. It keeps me up at night. Are you ready? Are you going to understand? We can’t be combative.”

In this divisive climate, however, educators have two options: develop discussion skills or risk students’ physical and emotional safety.

Ultimately, Wren says she avoids controversial topics in class.

“We’ve lost the art of disagreeing with each other in a respectful way,” Wren said. “So I go back and forth like, should I even bring this up in class? I want to make sure my students feel safe, not like what they or their family believes in is being attacked.”

There’s no perfect solution, especially given that this toxic discourse permeates our national government, too.

On Jan. 15, the U.S. House of Representatives voted 228-193 to send two articles of impeachment against President Donald Trump to the Senate, where he now awaits the outcome of the trial for potential removal from office.

As the impeachment process continues, tensions between the two parties skyrocket. According to FiveThirtyEight as of Jan. 27, 83% of Democrats support impeachment. By stark contrast, only 10% of Republicans support impeachment. Further, the Senate vote is expected to be split almost evenly amongst party lines.

Look at any major current issue, and the divide is clear.

Take immigration, for instance. Regardless of personal belief, the two opinions on immigration making headlines are undoubtedly and utterly opposite: completely abolish Immigrations and Customs Enforcement (ICE), or completely bar undocumented immigrants from the U.S. through Trump’s “zero-tolerance” policy.

It’s not even about immigration reform anymore. It’s become an all-or-nothing game, with zero room for compromise.

Government teacher Robert Orr says he doesn’t know of a perfect way to overcome split politics, but encourages us to approach disagreement with sympathy, rather than aggression.

“We need to remember that our kids, Americans, and non-citizens as well, are going through real stuff,” Orr said. “We need to take a step back and be sensitive.”

It wasn’t until my freshman English teacher pulled me aside one day that I finally understood this. She gently suggested I be more understanding and aware of how I expressed myself. She told me that having strong opinions was okay, but that it didn’t grant me the right to suppress those different from mine.

Now that I’m a senior, I’m overwhelmingly grateful that she cared enough to speak with me about my behavior.

However, I also recognize that she is just one person, in one specific instance.

It is a teacher’s role to act as a facilitator. But in classrooms with nearly 40 kids, the responsibility of civil political discourse falls on us, the students.

We are human beings with complex emotions and unique experiences. We aren’t always going to agree. Regardless, we must make the effort to tolerate and care for each other.

The topics we argue over aren’t unimportant. We shouldn’t ignore controversy to promote false unity. Rather, it is with sensitivity, patience, and compassion that we must discuss these issues.

We are the rising generation, the future. The fate of this country rests on our shoulders.