Senior debate captain Astor Redhead admits he wasn’t the best debater his first three years of high school. Although he competed almost every other weekend last year, piling about 140 rounds at tournaments, he just wasn’t that successful.

“40 hours of work, and I didn’t even make it to elimination rounds at all my entire first semester,” Astor said. “I think that was probably the hardest part, spending so much time working really hard and still not advancing.”

Things took a positive turn second semester, though, when he qualified for the national championships with his debate partner Serkan Tan, becoming the first FUHS public forum debate team to reach the Tournament of Champions.

How did they find success? Well, finally learning the rules of debate sure helped.

“What took my partner and me so much time to do well in debate elimination rounds was that we had to discover and teach ourselves how debate actually works,” Astor said. “For every tournament we would leave it wasn’t so much, ‘Oh, we didn’t have evidence for that.’ It would be, ‘Wow, I didn’t even know that rule of debate existed.’ I literally went three years without knowing you had to respond to things and you had to defend case and rebuttal when the point of the speech is supposed to be attacking your opponent’s case.”

Instead of selfishly capitalizing on what he’s learned, Astor has turned his successes—and failures—into an opportunity to teach others. Although still a student, Astor serves as the FUHS Debate Team Captain.

He supervises about 14 students, including junior Lauren Cagley and freshman Audrey Bae, who were terrified of competing in their first tournament in October. So, he helped them take control of their performances.

“Their big issue was that they didn’t know what cases to read in the rounds,” Astor said. “So they called me at 5 p.m., and we wrote an entirely new case for them about opioids and how Medicare For All can substantially reduce opioid addiction and the opioid epidemic.”

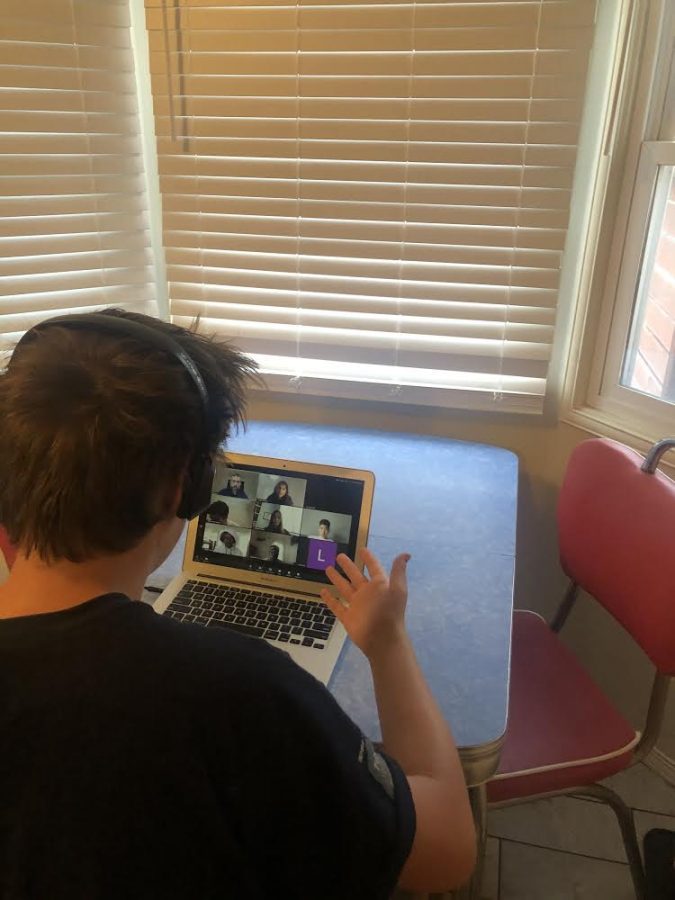

Lauen says that online platforms like Zoom have made practice and prep before a tournament much more convenient. “We can compete in tournaments across the country and we don’t have to pay to actually go there,” she said.

Her debate partner Audrey agrees: “I can just hop on instead of having to drive 15 minutes to Fullerton and attend practice or go to school or a tournament.”

But Lauren has noticed some downsides.

“I feel it’s almost like a double-edged sword,” she said. “I think me and Audrey were both having fun going to tournaments almost every weekend, but we’re completely exhausted once tournaments end.”

Audrey says students are also coping with the stress of competing online.

“In our most recent tournament, my wifi completely went out in the five mile radius that we were in, so in our first round I had to call Lauren over the phone, but my connection is absolutely terrible because of where I live and my reception does not always go through,” Audrey said. “So Lauren had to hold up her phone when I was giving my speech to the computer’s mic so that they could hear my voice.”

Audrey said they used 40 minutes of their round time just dealing with technology issues.

“Then on to the next round, my parents and I had to hitch a ride up to 40 minutes away so I could go to my cousin’s house so I could finish Round 2,” she said. “Then, I had to move again to my aunt’s house because we couldn’t stay at my cousin’s house just to finish Rounds 3 and 4!”

Although Astor can’t solve the new debaters tech issues, he has helped students reduce tournament anxiety by fully preparing them for what they can control—their performances.

Now that he’s a coach, Astor believes that it is a much different experience than simply being a team member. Since motivation in debate was lacking last year, the pressure was on him to bring back that motivation for Public Forum performances.

Fortunately, he’s delivered and takes a lot of pride in being the captain. “But I think as a coach, it’s much easier in the sense that I have freshmen who I want to do well. And I recognize that when I was a freshman, I really wished someone would have coached me,” he said. “I recognize that I actually can have an impact on these people and help potentially improve their high school careers.”

Redhead says that teaching debate has forced him to analyze the process more closely. “As I’m re-explaining [rules] and teaching them to the new debaters, I’m viewing them in a much different way. Like when I teach the very fundamentals of debate, it reminds me that they exist,” he said.

Some of the fundamentals of debate, like invisible rules and effective debating, can play a vital role in a win or loss. Astor himself learned a lot from his judges’ feedback after a round ended. “Because of that, you know objectively why you lost the round, meaning afterwards you can go, ‘Okay, I messed up on responding to a certain type of argument.’”

After going to a debate camp and doing hours of research a day on debate cases, being a debate coach has become a comfortable fit for Astor. “I love it because it’s objective,” he said. “You lose the round because you messed up, not just because your opponents were better.”

Redhead says the best way to practice is to simulate an actual debate. Set up two teams. Two people per team will take either the Affirmative or Negative side of a specific issue, such as Medicare For All or a No-First-Use Nuclear Policy, and debate over the topic. Afterwards, Astor will tell them, “Okay, you objectively lost on these arguments and the other team objectively lost on these arguments. Here is what you did wrong, and here’s how you can improve it.” A few days later, he will then meet one-on-one with students, and say something along the lines of, “Oh, on our last debate, I told you that you lost on this type of argument, now let’s spend two or three hours just having you give that same three-minute speech in every different way, to go over this one different type of response and how you can respond to it.”

Astor clocks a lot of hours as a coach.

“Friday nights before a tournament, I’m going to have someone call me at 5 p.m. and I’m going to work with them and be on zoom with them all the way until 1 or 2 a.m. prepping them for the next morning,” he said.

“Yeah, so I think the fact that I have experience in debate, and I actually know what’s going on, is definitely laying the groundwork so that everyone knows how debate actually works,” Astor said. “Even when I’m gone, they’ll at least have the foundational work to be able to improve.”

Staff writer Lamya Saade contributed to this story.