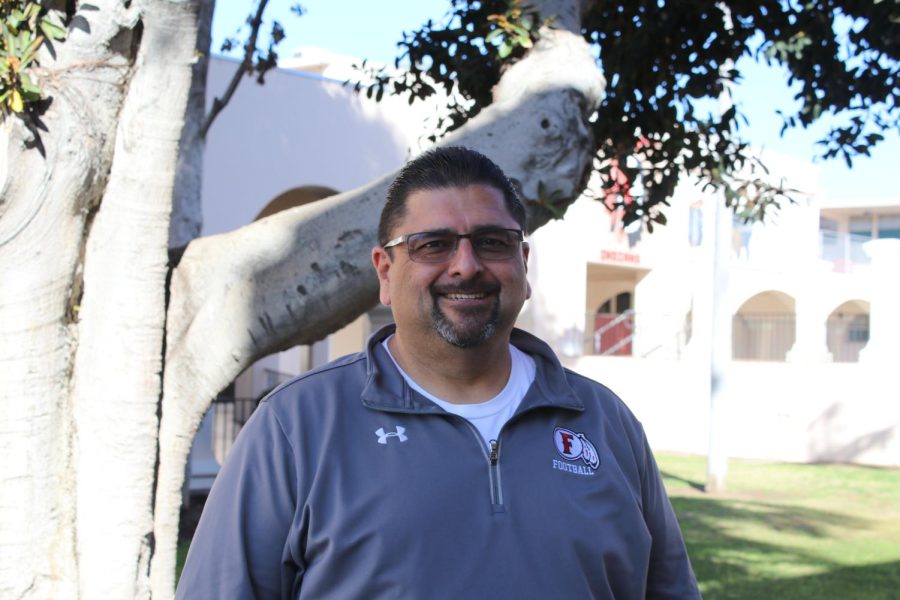

Athletic director Joseph Olivas is driven by two voices. The men of his family say, “Work hard, be tough and keep going because no else is going to help you,” while the women of his family say, “Be respectful, kind and gentle.”

And it’s finding the balance between toughness and compassion that has earned Olivas the honor of Teacher of the Year. Every year, teachers and staff nominate and vote for whom they think is most deserving of recognition.

As an athletic director, special education teacher and assistant football coach, Olivas has a lot to juggle. “I have my teaching job. I have 23 athletic programs to manage. I have at least 650 students,” said Olivas, who has taught at Fullerton since 2006. “I’ve got to make sure the referees get paid at five o’clock. I’ve got a lot to do.”

Assistant principal Jon Caffrey says Olivas doesn’t quit until the job is done. “Many times I have seen him leaving the office after 10 p.m. and back at it the next morning at 6:30 a.m.” Caffrey said. “He loves Fullerton High and has shown an amazing connection to our community.”

Those long hours have been complicated by the pandemic. In addition to regular scheduling duties, Olivas has dealt with last-minute cancellations when opposing teams have had players test positive for COVID. Scheduling make-up games can be a nightmare.

Football coach Richard Salazar says that Olivas has been a good fit for someone who needs to manage an ever changing schedule. “I’m leaving late myself but he’s here doing athletic director stuff,” Salazar said. “He’s here at the games. He’s a definite organized individual. He likes to plan ahead, way in advance. He gets ahead of a lot of things.”

Olivas says he didn’t always see himself as a teacher. Initially Olivas took classes to become a child psychologist, but he realized that private psychologists don’t reach as many kids as teachers.

“Only people with a lot of money are going to be able to see a private psychologist, but those aren’t the only kind of kids that want to help,” Olivas said. “So I kind of reevaluated what I was looking at and I realized I need to work in the schools.”

As a special education teacher, Olivas said he’s comfortable working with students with disabilities. “I have a sister who has cerebral palsy,” he said. “As a little boy, I went to [physical] therapy with my sister and I would see what real kids with disabilities look like.”

Olivas was coaching football at Artesia High School in 1996 when he was invited to teach his first special education class.

“I’m in the football office and the principal walks in and he’s going crazy in a panic,” Olivas said. “The principal says, ‘‘Hey, I need, like…’ then he points to me and asks, ‘What do you do?’ and I say, ‘I’m the offensive and defensive line coach.’ He goes, ‘no, no, no. What kind of degree you got?’ I say, ‘I have a kinesiology degree.’ He goes, ‘Do you want to teach handicapped kids science?’”

So, looking as young as some of his students, Olivas arrived with an emergency credential to teach his first special education class. “I was expecting to see kids with crutches, wheelchairs, body casts, helmets to protect their skulls, but I walked into a room with a bunch of typical teens just hanging around,” he said. “I just sat down and the students thought I was one of them. And then I heard one dude say, ‘Where’s this fool at? Where’s this teacher, where is he?’ And I go, ‘I’m right here.’ Oh, they got freaked out. But we broke out the books, and I got good at teaching.”

Olivas admits he had his fair share of mistakes in the classroom. To engage students, he invented a game where students were invited to throw paper balls at a person who answered a math question incorrectly.

“They started figuring out their math, so I’m, like, awesome! Well, actually, no. One of the guys took a stapler, wrapped it in paper and when I answered a question wrong, he threw it at me. I got hit and I wanted to destroy him. Then, he said, ‘Hey, but it’s your game!’” said Olivas, who said he’s had many great mentors to help him through his mistakes.

Olivas says that teaching is a good profession that allows him to provide for his family. Although teachers are known for being underpaid, Olivas says as a teacher in Fullerton, he is satisfied with his ability to take care of his family.

His daughter Victoria recently needed an MRI for her knee injury. Even though the procedure wasn’t covered 100% with his insurance, he was happy to pay the difference.

“The doctors asked, ‘You sure you want to do it?’ I say, ‘Where do you want me to write the check? My kid needs this. I did my job, I got a career, I got the money. Give my kid what she needs.’”

Olivas earned his Bachelor’s degree from Cal State Long Beach, his special education degree from Cal State San Bernardino and his Master’s from Whittier College. Olivas is proud to be a teacher, especially because he admits to being a bit lazy as a kid. Becoming a hard worker was something he had to learn the hard way. His war veteran grandparents made sure he grew up resilient.

“I was with these old cranky men who had seen horrible things in war. So being a sissy and not doing your job was not an option,” he said. “I fell through a roof one day while I was helping them fix a roof in east LA. And after I fall through, they go, ‘Well, you gotta get up.’ And I’m, like, ‘You gonna come and get me?’ And then they just kept working and I was, like, ‘Okay, I gotta get up myself.’”

Senior Franklin Honrado says Olivas has high expectations for his football players. “All the times he yelled at us during football, he always told us it wasn’t to be mean but it was to make us better,” Honrado said. “It was to become our better selves, not just in football, but outside too. I respect him for that.”

Salazar said he was glad when Olivas was available to coach. “I knew he knew how to push kids, how to demand excellence and that’s someone I wanted to be a part of my staff,” Salazar said.

Olivas’s daughter Victoria is a junior at Fullerton. “As a person and a player, I would say that he helped mold me into someone stronger and capable of doing anything that I put my mind to,” she said.

Victoria says that her father is nice to everyone. He doesn’t treat her differently than other students on campus. “Honestly, I think he treats everyone like they’re his child,” she said.

Reporter Valeria Macedonio contributed to this story.